What American Idol Can Teach About Presenting to Execs

November 26, 2012How to Create a Custom Color Palette in PowerPoint

December 21, 2012I read a lot of research papers on the most effective way to present information. So I was intrigued, and then disappointed, to read this paper testing one model, called the Assertion-Evidence model.

The study appears to prove picture slides with a full sentence slide title are more effective than bullet point slides with a topic title – at least for complex concepts. However, the research is badly flawed and the conclusions drawn are overly broad and even biased.

In this blog post, I want to review what the research purports to say, why those conclusions are skewed by poor research design, and what the research actually says.

1. Research Results

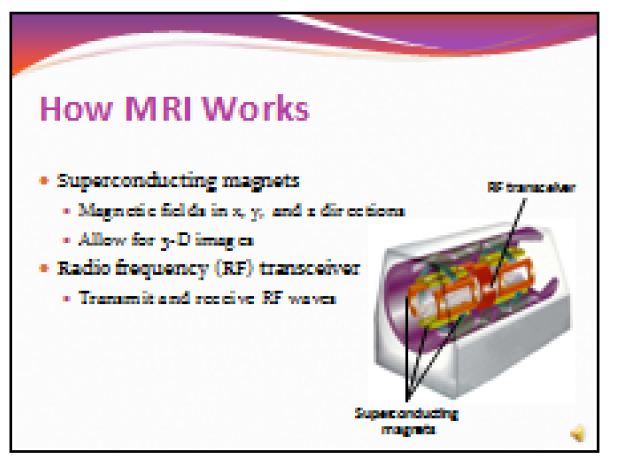

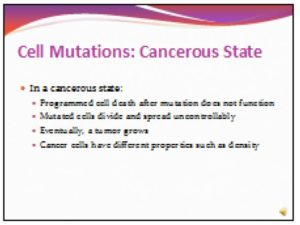

In 2006 Michael Alley, author of The Craft of Scientific Presentations, first proposed the Assertion-Evidence model for building slides, where the slide uses a full sentence slide title (the “Assertion”) and then a picture with limited text as the slide content (the “Evidence”).

In 2011, Alley continued studying the A-E model, comparing it against the Topic-Subtopic model; the typical PowerPoint model that uses a brief topic slide title and a list of bullet points, often including a relevant picture.

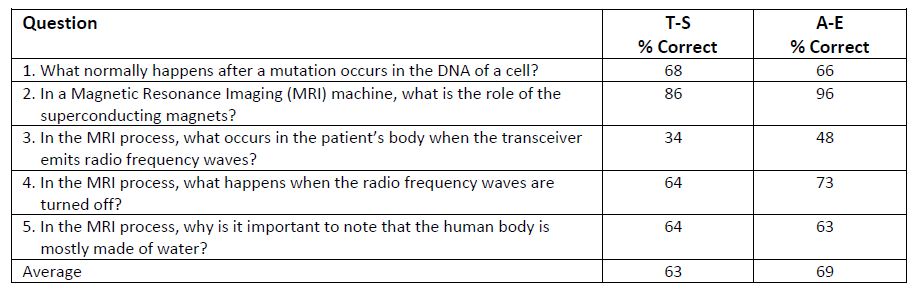

The results show that, for “complex content”, students learned more from the A-E slides than the T-S slides. On the other hand, they remember statistics better when they are on the slide than when they are simply spoken by the presenter. Alley draws the following conclusions

1. The A-E model is superior to the T-S model for complex content

2. The A-E model and T-S model are similar for remembering statistics, as long as they are included as text on the slide

3. The T-S model is superior for remembering secondary facts that are written on the slide, rather than merely spoken. However, this comes at the expense of understanding complex content

These conclusions are misleading and based on faulty research design. Now I look at the flaws in this research study and propose a new set of conclusions.

2. The Flaws

Michael Alley and his colleagues are to be commended for breaking new ground and testing different models to find the best way to use PowerPoint for educational purposes. My critique of his research is not to be negative, but to caution readers against rejecting other models that might serve your purposes even better.

The main problem with this research is the T-S slides were a mix of two types of slides: Type 1) slides with text only and Type 2) slides with text plus a relevant picture. In this study, 6 of the 11 T-S slides were Type 2 slides.

These Type 2 slides are pure poison. Poison! We’ve known for the past 10 years presenting a slide that combines extensive text plus a picture harms learning. This principle – called the Redundancy Principle — has been proven in studies by both Richard Mayer and by John Sweller.

The researchers should not have combined text-only and the poisonous text-plus-picture slides into the T-S model. This just gives an unfair advantage to A-E slides that isn’t even worth testing.

Instead, they need to test the A-E model against three other models, which have NOT been proven to harm learning.

1. Full sentence title and text-only

2. Topic title and text-only

3. Topic title and picture-only

Another flaw is the apparent researcher bias. Their goal appears to be to prove the A-E model, not objectively test its merits. This is a shame. The A-E model looks promising, but it’s only by being intellectually honest they will discover its limitations and improve it further.

Consider the way they ignore data that doesn’t support the A-E model. The students wrote a test that included five multiple choice questions. Using the A-E model, students did better on only three questions. What did the researchers do? They ignored the other two questions and only analyzed the three questions (questions 2-4) where the A-E model was superior.

Consider also how the researchers dismiss the fact that students remembered statistics better on the T-S slides, based on fill-in-the-blank questions on the test. The A-E slides do not contain those facts as written text, only as spoken text by the presenter. The researchers dismiss it as not important enough to offset the advantage of A-E slides for learning complex content, rather than unemotionally acknowledge the superiority of T-S slides in some learning situations.

3. The Real Conclusions

You cannot draw conclusions when the two slide models have so many things that are different. Are the higher scores because of the poisonous Type 2 slides? Or the superiority of pictures over bullet points? Or the full sentence slide title? Or the animations only included on the A-E slides? Which of these actually explains the difference in performance? It’s impossible to know for sure.

But some things you can conclude are:

1. For important statistics, include them as text on a slide, not spoken text. Students remembered statistics better when they were included as slide text, rather than simply spoken by the presenter. This suggests there will be times slides with a lot of text will outperform slides with limited text and pictures.

2. Pictures don’t help students remember statistics. When the slides contained the statistics as text, students did just as well with the A-E slides and the T-S slides. The focus on pictures did not give the A-E slides an advantage.

Both of these conclusions argue AGAINST the A-E model when the goal is to remember statistics. Instead, they recommend a focus on slide text over images.

I applaud Professor Michael Alley for continuing to test and refine the A-E model as a promising direction for educators and other presenters. I encourage him to continue studying the A-E model to discover the elements that improve learning and the conditions where the A-E model is superior, as well as inferior, to other models.

Unfortunately, the only conclusion we can make from this study is that students remember statistics better when they are included as slide text than when they are spoken by the presenter or presented as a picture. The rest of the conclusions must be discarded because of the research design flaws.

About the author: Bruce Gabrielle is author of Speaking PowerPoint: the New Language of Business, showing a 12-step method for creating clearer and more persuasive PowerPoint slides for boardroom presentations. Subscribe to this blog or join my LinkedIn group to get new posts sent to your inbox.

2 Comments

Bruce,

Excellent article as usual. I appreciate your diligence in looking beyond Alley’s assertion and examining the evidence.

Just one small quibble: I believe what you called the split attention effect is actually the redundancy principle.

Jack – Thanks for the comment. Great to hear from someone to knows the literature.

You are correct and I’ve updated the article. The split-attention effect (Sweller) refers to a printed piece where the text and picture are visually separated and the eye has to flick back and forth to match them up. The Redundancy Principle (Mayer) adds voice to the split-attention effect, increasing cognitive overload. In both cases, learning is harmed.

—

Bruce Gabrielle