The Greatest Storyteller of All Time Is ________

March 9, 20133 Steps to Turn a Graph into a Story

April 8, 2013Some critics have come crashing down hard on pie charts. Edward Tufte says “the only thing worse than a pie chart is several of them.” Stephen Few says “save the pies for dessert“. Cole Nussbaumer says “Death to pie charts.”

Well, they are all wrong. Pie charts deserve your respect. And I’ll tell you why.

First, let’s consider the critics’ valid criticisms:

1. A bar chart allows more accurate comparison than slices in a pie chart

This is true. But not every chart is about making precise comparisons. Sometimes you only need approximate values so you can engage in a discussion. It’s not necessary to see that one slice is 1% larger than another slice to have that discussion.

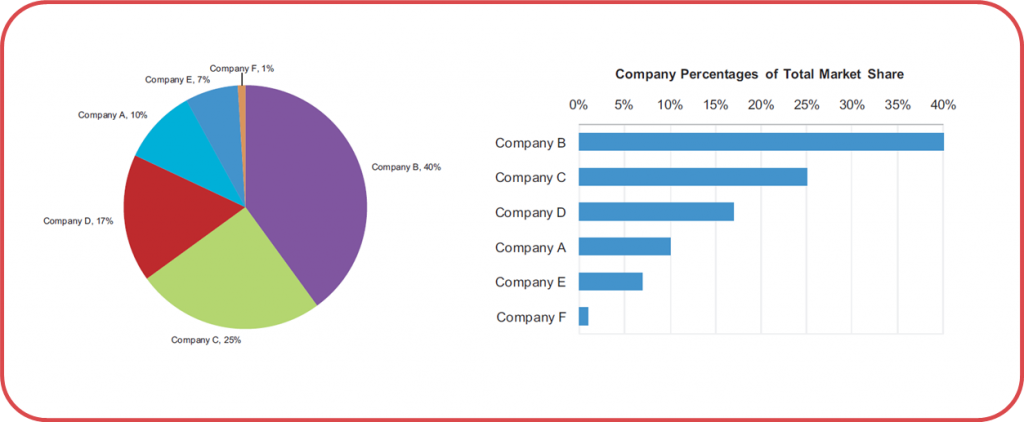

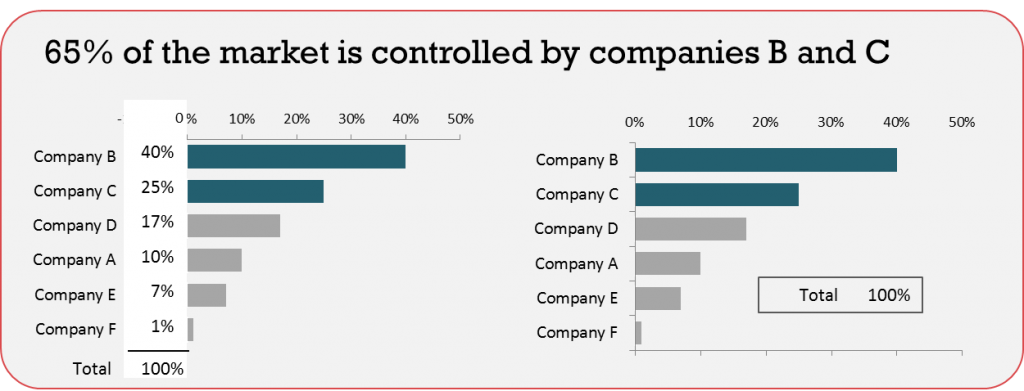

For instance, take this pie chart from Stephen Few’s article. Clearly, a bar chart gives more precise comparisons.

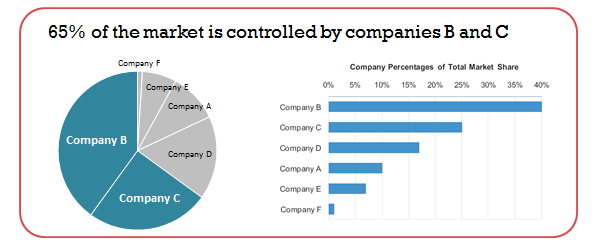

But what if, instead, the only point you want to make is that the 2 largest distributors control 65% of the market. Which graph demonstrates that more clearly?

Few admits there is research (Spence and Stephan Lewandowky, 1991) demonstrating pie charts are superior in this case, but he assumes this is a very “rare in the real world”. On the contrary – this is extremely common in business presentations where the goal is to tee up issues for discussion, not just lay out the data for detailed study and comparison.

In fact, if you sort your pie slices from largest to smallest, you don’t need to depend on visual comparisons. The ordering tells you which is larger, right?

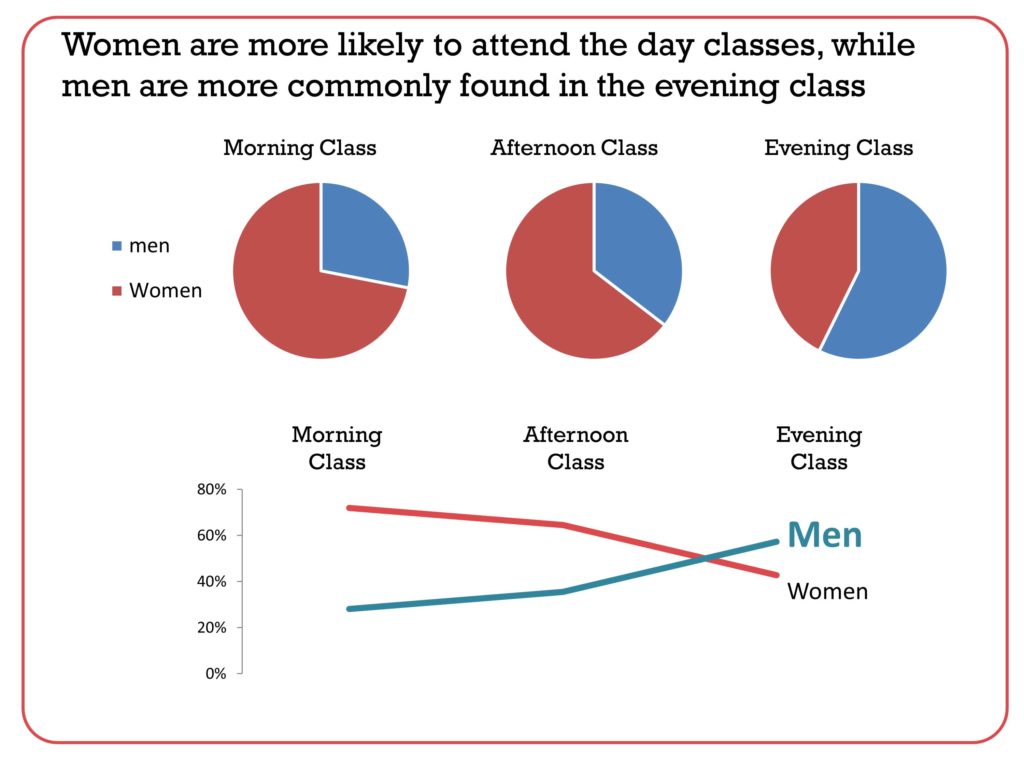

2. A line chart shows trends more clearly than side by side pie charts

Again, this is often true. But it depends on the data you have, as well as the impact you want on the audience. Certainly a pie chart with 10 slices is difficult to compare over time. But what about a pie with just 2 slices?

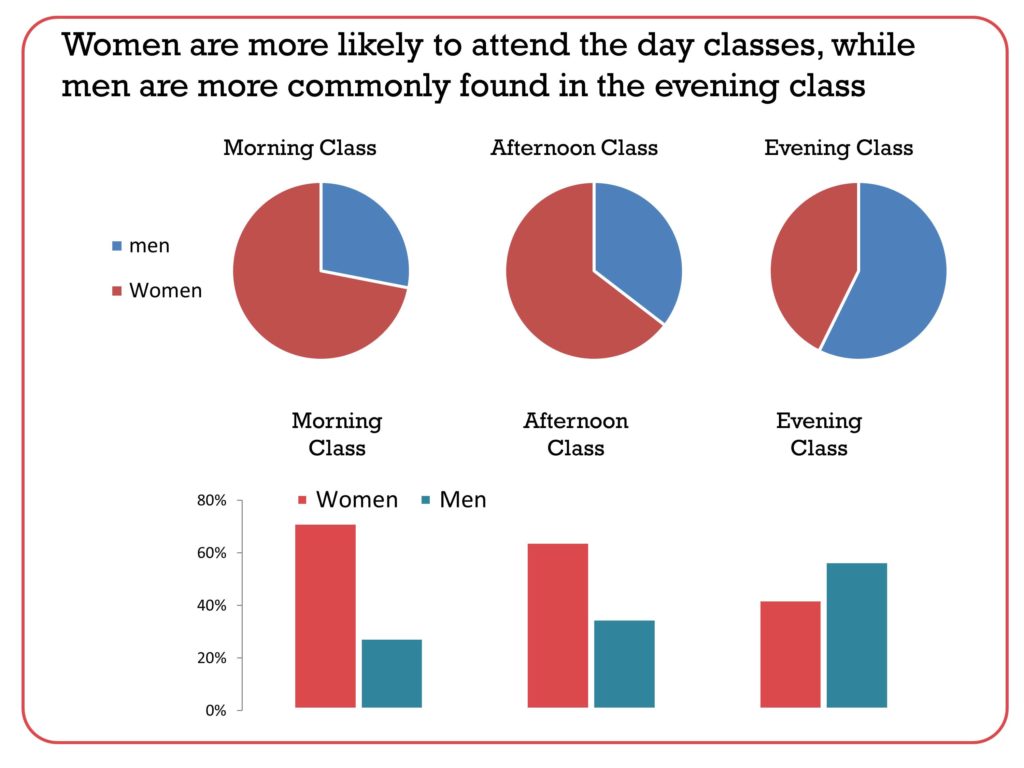

Tufte’s dogma often unravels when you press on it just a little. He argues you cannot accurately see trends when you compare pie charts side by side. In fact, pie charts CAN be a better way to visualize side by side data when the data is simple. And when you’re comparing percentages, bars are NOT more accurate than pie charts. Look at these two displays. Which one communicates more quickly?

In this case, a pie chart is not hard to compare. But what about a line graph? Certainly, it does the job. But there’s also a bit of confusion. Because we are referring to 3 separate events and how they differ. A line graph communicates a smooth continuation of changes throughout the day. That isn’t quite what we are saying and so it takes a bit of mental gymnastics for the reader to adjust the line graph to its intended meaning. The criss-crossing lines also introduce a bix of complexity.

In fact, despite some of the valid reasons to avoid pie charts, there are also valid reasons pie charts can be SUPERIOR to line charts and bar charts:

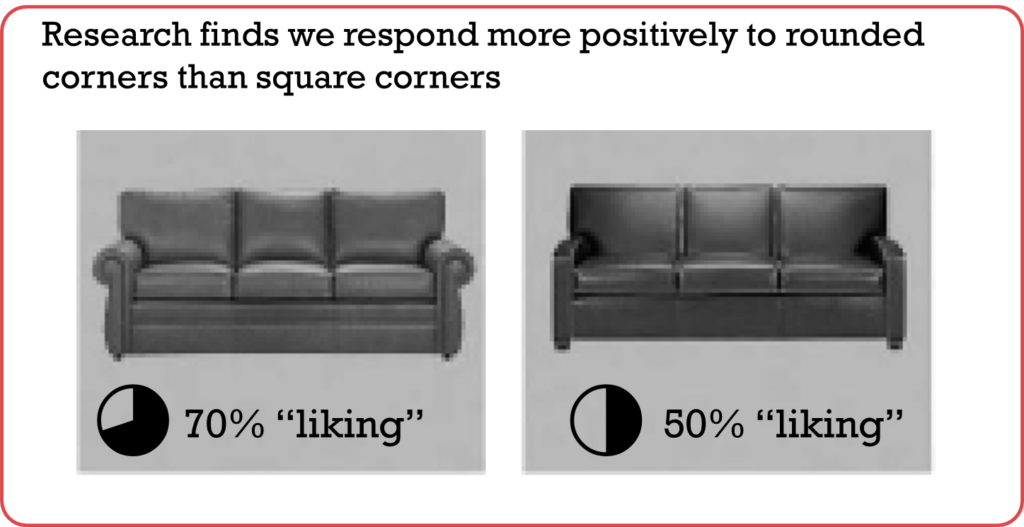

1. Puts the audience in a positive frame of mind

Perhaps most importantly, the visual system LIKES round things more than sharp angles. Research finds our emotions are more positive to rounded corners than sharp corners. No matter how accurate your data, you cannot deny bar charts are just BORING to look at. Or, at least, more boring than pie charts.

Some in the hard-core scientific community do not recognize emotion as a valid reason to use pie charts. That’s understandable given their mission of presenting data truthfully and accurately.

But great presenters have a different mission: to simplify ideas and motivate audiences. And they know that precise logic and measurements are not enough; you also have to appeal to them emotionally. Pie charts help put the audience in a positive frame of mind.

2. Communicates part-to-whole relationship better

At a glance, you know a pie chart is splitting a population into parts.

Bar charts do not have the same meaning. You can signal to the reader the bars add up to 100%, by adding a column or an annotation. But this requires some extra mental gymnastics by the reader to understand the bar chart represents 100%. Nothing beats a pie chart for instantly communicating 100%.

3. Easier to estimate percentages

Research shows that it’s easier to estimate the percentage value of a pie chart compared to a bar chart. That’s because pies have an invisible scale with 25%, 50%, 75% and 100% built in at four points of the circle. And the angle of the pie’s interior corner provides an additional cue not available in unlabeled bar charts.

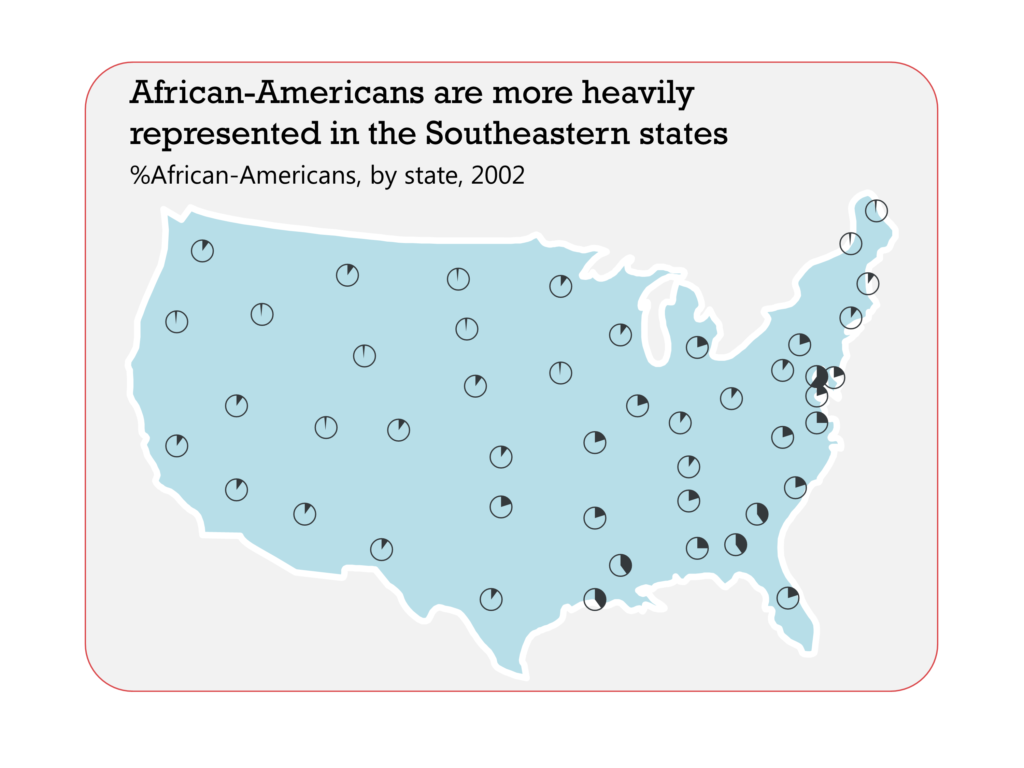

Especially as pie charts become smaller, and you need to use a lot of them, pie charts can communicate percentages much more quickly than bar graphs. See for yourself. (here’s another example)

Tufte is wrong to make an assertion about pie charts based on his own context (the analysis and presentation of complex data) and use broad strokes to apply that to domains where he has no expertise (presenting and selling ideas in the boardroom). Pie charts have earned their place in your business presentations.

Tufte is wrong to make an assertion about pie charts based on his own context (the analysis and presentation of complex data) and use broad strokes to apply that to domains where he has no expertise (presenting and selling ideas in the boardroom). Pie charts have earned their place in your business presentations.

So, take some advice from someone who presents data to executives. Use pie charts

- When you want to affect your audience emotionally

- When you want to quickly communicate a part-to-whole relationship

- When approximate values are enough to have a productive discussion

And my advice to Tufte? Pick up a copy of my new book, tentatively titled “Storytelling with Graphs” for a more balanced and practical view of the role of graphs in visual communication. I’m hoping to have it released this summer.

About the author: Bruce Gabrielle is author of Speaking PowerPoint: the New Language of Business, showing a 12-step method for creating clearer and more persuasive PowerPoint slides for boardroom presentations. Subscribe to this blog or join my LinkedIn group to get new posts sent to your inbox.

112 Comments

Brilliant, thanks Bruce. So clearly conveyed as well.

Jon – thanks for the kind comment. Glad you enjoyed the article.

—

Bruce

I agree, Bruce.

Out of curiosity about why Tufte so hates PowerPoint, I actually paid for and went to his seminar (which comes with all his books).

In short, his world is that of one, flat graphic that is data dense (and therefore how to represent that dense data, sans narrator, is the center of his target). In other words, graphical documentation.

Unfortunately he lambastes PowerPoint and presenters without conceding that there are different, albeit radically important, distinctions between those modalities.

Keep up the keen work.

Roger

Thank you Roger and I appreciate the perspective of someone who has attended a Tufte lecture.

I think Tufte has done a nice job of analyzing and commenting on data-dense graphics (and I’m talking hundreds of data points, like astronomical maps). The problem, as you point out, is his inability to make allowances for any other type of use. My goal with writing this article is to help people feel better about using pie charts in certain situations, which can improve their communication effectiveness.

Hope you’ll visit the blog often.

—

Bruce

“Astrological maps” are your idea of rich datasets?????? You do understand that astrology is a field utterly devoid of actual data, right?

At least you aren’t defending perspective pie charts (or is that a follow-up post?)

Keith – thanks for your comment. Of course, I meant “astronomical”. Although, astrology is based on numbers (years, months and dates) so not completely devoid of data.

I haven’t seen any research showing 3-D pie charts are good for any purposes, but if I do you’ll read about it here.

I secretly love pie charts, and I am a bit ashamed of it considering how much they are hated by gurus like Tufte. Actually, I like rounded charts, every radial chart gets my attention.

I wonder though if the better solution to compare values and emphasize a market share (your first point) would not be a single bar chart : more precise and allows you to see the largest contributors easily. Thanks for your article !

(and sorry for my english, which is not my mother tongue)

“But what if, instead, the only point you want to make is that the 2 largest distributors control 65% of the market. Which graph demonstrates that more clearly?”

You’ve used an entire slide for one fact. Don’t bother with a chart.

The audience will have follow up questions: Who are they? Who makes up the other 35%? They will read the annotations to see in which country this research was done. As they discuss it, it will be helpful to have a visual in front of them. After the meeting, the PowerPoint slides will become a document that others will read on their own. The chart is not a bother.

All of that information could be represented with a stacked bar chart with no more bother.

Yes, that’s true. Or a bar chart. Or a horizontal waterfall chart. Or a pie chart.

If you have to use multiple colors to represent one data series, you’re using the wrong chart.

Hi Patrick – why do you say that? You can use color to represent different categories, like countries or competitors, especially in a pie chart. How do you show different categories if not with color?

—

Bruce Gabrielle

Powerpoint slides become a document? If they are that text rich, no presenter is needed. If they are that text rich, no one will bother to read them while they are being “presented”..

Hi Bill – That isn’t correct. People can gather around data- and text-rich documents and have a discussion, ask questions, solve problems. A text-rich document give people more detail to react to, discuss and debate.

However if you’re just presenting data to people and aren’t having a discussion, then you’re right. Just email the deck and cancel the meeting.

I agree that for some very simple data samples, it’s more effective using pie charts than bar charts. When only two parts of the whole are compared, pie charts convey the information faster and more easily.

Another alternative to pie charts and bar charts, lying somewhere in between, are Stephen Few’s bullet graphs. Worth having a look at them.

I find the bullet graph quite challenging to understand at a glance. Perhaps it will take some time for it to become learned and so intuitive to the audience.

A simpler version of the bullet graph is the progress bar chart – https://speakingppt.com/2012/02/16/show-percentage-vs-goal-with-the-progress-bar-chart/

Thank you for laying this out! I’ve made point #2 (part-to-whole relationship) to so many people, but they just default to guru and say “pie charts BAAAAAAD!”

Like all data visualization (and analysis for that matter), there is an art and a science. In the end, it’s about using any tool that communicates the point you are trying to make.

Yes, it’s the “pie charts BAAAAAD” mentality I wanted to challenge with this article. Dataviz gurus are not always right.

Hi Bruce,

Thoughtful article. I think the points you’ve touched on are valid concerns, and yet they actually are addressed in the Tufte books. It’s just the catchy sound bites that surface. What you’re addressing I think is, as you’ve said, the emotional band wagon that all pie charts are bad. We like them in appropriate circumstances – data is 1-5 parts of a whole that total 100% when combined.

At the end of your post you mentioned a new book, “Storytelling with Graphs.” Is this complete or still in progress?

Hi James – Good observations. I’m really just addressing the allergic reaction people have to pie charts. We need to remedy that with a more nuanced appreciation of when they are appropriate.

“Storytelling with Graphs” is still being written. It’s taking longer than I thought to tighten all the bolts. Hoping for a summer release.

—

Bruce Gabrielle

Pretty sure that just presenting the numbers would be better in every case there.

And what’s your argument to support that claim? Personal opinion? Or do you have something more?

Personal opinion, same as in the post; I’m not going to go through each example but.

First example: if 65% is the right level of precision, it’s only coming from the title. Off the pie charts, I can’t tell 65% from 60% from 70%. I can tell from the pie charts that it’s between 50% and 75% and then can sort of guess ~66%, but I don’t see how that’s more effective than putting “about 2/3” in really large font.

Last example: What are the percentages? I can kind of guess, and I assume that black/red means less than half vs. more than half, but beyond that, I’m lost without putting in some work. If the percentages are important, writing them out in place of every pie chart would be a much more effective way of conveying them. If the percentages aren’t important, then sure, use a pie chart.

Gray, my blog post is based on research, not personal opinion.

Do you present data to executives for a living? You will get laughed out of the room if you show a slide that says “About 2/3” in large font on a slide. They will say “where’s your data? who are these partners? who are the others? what’s the share for each? In which country? Are you measuring in units or dollars?” You need that on the slide or you will get interrupted with questions. It’s very likely you will not have just one pie chart on the slide, but perhaps different pie charts for each country.

I replaced the map slide with a better example. I hope that makes it clearer.

I missed the references to the research the first time I read the post. I looked again but all I saw was a link to a 2006 study that found some evidence that people preferred round objects to sharper objects. What is the other research supporting pie charts? In the first example, you said the pie chart was good for showing “65%” — your level of precision. Your follow up comment suggests that you really think that 65% is different in an important way from “about 2/3”. There is no way that there’s a study claiming anyone can distinguish 65% from 66.6% with a pie chart.

An analogy: everything I’ve read about cooking–every cookbook, every show, every recipe, etc–strongly suggests cooking filet mignon rare, and gives reasons that have to do with the cut, fat, flavor, etc. To me, your post and the subsequent discussion reads like someone claiming, “those recipes are flat-out wrong! You should cook filet mignon well-done IF you know that your guest prefers well done steak!”

That’s obviously true, and if that’s your point then I’ll concede it: if you strongly believe that your audience will prefer pie charts, you should probably use pie charts. But the flip side of your opening sentence, “some critics have come crashing down hard on pie charts…” is that some audiences will strongly dislike your pie charts. So it cuts both ways.

Again, if there’s research supporting your claims, I’d love to see it. For these examples, I found that the pie charts added no more information than was in the charts’ titles. So replacing the pie charts with just the raw numbers would have been a massive improvement.

Bruce, I think the most convincing example is the one with 2 large distributors controlling 65% of market share. The pie chart does stand out more. However, I think your comparison with the bar chart is incomplete and therefore incorrect. You used an additional color for the pie chart, highlighting the 2 largest market shares, and did not use the same color coding for the bar chart. Had you used the same color coding for the bar chart, I would argue that the bar chart would convey your point more effectively than the pie chart.

I think your comment “do you present data to executives for a living?” is so ridiculous. Every time you decide to use a pie chart, keep in mind that there is a more effective way to present the data. That’s the point, I have never found a pie chart to be the best solution, which is why I never use them and insist that any presentation or report with my name on it does not make use of them. They are tacky and weak at conveying information. And by the way, lots of people present data to executives for a living, it’s called business.

Hi Nick – You’re wrong. The pie chart conveys total percentage better than a bar chart (even Stephen Few admits this in his article). There have been studies done to prove this. I also run this study in my workshops and pie charts are always more accurate than bar charts or stacked bar charts, even when color-coded. Always.

Not everyone presents data to executives for a living, Nick, so my question wasn’t “ridiculous”. People who don’t present to executives aren’t aware how quickly pie charts communicate, how effectively they tee up issues for discussion and how much more visually engaging they are. How could they know?

You’re also incorrect that pies are tacky and weak and every time you use a pie chart there are more effective ways. That’s narrow-minded and ignorant. Not my opinion, but research says so loud and clear. Wrong on every point, Nick.

Gray, The point that Bruce is making in this article is all related to allowing your audience to ‘get the message faster’. If preciseness is not the requirement (which often is the case) then replacing a pie chart for a bar chart is perfect.

Track your eye when looking at the comparisons and see how much longer it takes to work out the message with the bar chart.

From my experiences of creating visuals that work fast I totally agree with Bruce.

I agree the bar charts don’t work well here and I’m no ta fan of them in general. For these examples, I’d get more information faster with just the raw numbers (in most of them, a table). When precision isn’t important, it matters less. But it isn’t clear from the post and the comments whether that’s Bruce’s point.

Yes, agree

You’re comparing apples and oranges to make Tufte look wrong. If your goal is to compare PERCENTAGES, not amounts, a stacked bar chart showing percentage breakdown is the right thing to be comparing, not multiple bars. Of course multiple bars don’t show percentages. But pie charts don’t show amounts. False comparison.

Stacked bar charts are a bit better than pie charts because we’re better at comparing lengths than angles. And side-by-side they take up less space. So your argument comes down to “people like looking at round things”. Oh really.

Pie charts are certainly good when combined with a map, when there’s just one percentage to convey: http://sciblogs.co.nz/picturesofnumbers/ But that’s pretty uncommon.

Mike – thanks for the comment. I visited your blog and you have some nice data visualizations and commentary. I’ll probably spend some reading time there.

I agree with you that when it comes to accurately comparing two values, a bar chart/stacked bar chart beats a pie chart. You have 3 claims I’d like to address:

1. I’ve selected a horizontal bar chart vs pie chart to make Tufte look wrong. Not true. These two charts were selected by Stephen Few and I’m using them to refute his claim that pie charts are rarely useful. No effort was made to purposefully select bad graphs to make Tufte look wrong.

2. A stacked bar chart is better than a pie chart for comparisons. Again, this is only true when the goal is precise comparison of two values (eg. which is larger when looking at two bars in stack vs two pie slices). When the goal is to estimate the percentage of a whole, the pie chart is better than both a bar chart and a stacked bar chart (Hollands and Spence, 1998)

3. My argument comes down to people like looking at round things? No, that’s just part of my argument, and a critical point because when your paycheck depends on convincing audiences, you need every tool at your disposal to put people in a positive frame of mind. The rest of my argument is that pie charts are better than bar charts or line charts in many situations: when you have just 2-3 pie slices, when the goal is to instantly communicate 100%, when one pie slice is clearly larger than the others.

There are a lot of people who hate pie chart. HATE them. My goal is writing this article is to reassure them pie charts can be useful in many situations.

I disagree with your suggestion that you are making a fair comparison here. I don’t see your second comparison (that the top 2 companies ~65%) anywhere in Few’s linked article. If you are making the comparison Few is discussing, the bar charts are clearly superior; if you are making the second comparison, the stacked bar chart is clearly superior to the pie chart. Different comparisons suggest different charts, but in both cases pie charts are clearly inferior.

I’m making the second point. And a pie chart is superior to a stacked bar chart in that case. See research by Hollands and Spence, 1987 or Spence & Lewandowsky, 1991. Both studies (and others) measured how accurately people could add two slices of a pie chart or a stacked bar chart. Pie charts were superior to stacked bar charts.

“[W]hen your paycheck depends on convincing audiences,” then, sure, maybe you should use pie charts—but you also shouldn’t pretend that you’re in the business of making good data graphics, which are those that allow the viewer to quickly begin spatial or visual reasoning about the information rather than just be consuming it (however quickly the latter may happen).

Rather, you’re in the business of persuading people, for which it is preferable that the viewer *not* be reasoning, so making good data graphics can only work to your detriment. I’m sure you’re crying all the way to bank if you’re any good at it, but you couldn’t fault Tufte or Few or their admirers for having a low opinion of your intellectual integrity when your object is to convince rather than enlighten.

Hi Jake – thanks for your thoughtful comments. I always enjoy a rousing debate about pie charts.

You seem to have a contempt for the area of persuasion but high regard for the area of information. Why is that? Perhaps you believe that good data speaks for itself. And in many cases that is true. If you are monitoring quality control, for instance, an unbiased dashboard which accurately detects small variances from normal is better than a pretty dashboard with lots of shiny objects. In this situation, bar charts perform better than pie charts. We agree on that.

But Jake, isn’t there is a world outside of information visualization, where persuasion is just as, and sometimes more, important than detecting small variances? Isn’t there? Because in that case it doesn’t matter if our 35% market share has fallen to 30% or 28.9% or 27.2%. The point is that it’s fallen sharply. And we need to do something about it. The goal here isn’t the same as the information dashboard. It’s to rally emotion. It’s to waken sleepy executives and get them to take action. It’s to say “Our competitors are eating our lunch!”. And a pie chart gobbling up their dwindling market share may send that message more effectively than a bar chart. We seem to disagree on that.

That isn’t to say persuasion is more important than reason, Jake. Quite the opposite. Persuasion and reason must WORK TOGETHER. 2,500 years ago Aristotle said there are three things you need in order to move an audience: reason, emotion and credibility. And every great salesperson, politician, lawyer and executive knows that. You don’t really believe that people are reasonable, do you Jake? The stock market proves people are not reasonable. Dan Ariely’s book “Predictably Irrational” trots through dozens of studies showing people are not reasonable. Logic only gets you so far, Jake. And if you are just presenting the market share data, and don’t care what the executives do next, then go ahead and use bar charts. They are indeed more accurate.

But when you want to MOVE your audience to ACTION, emotion is critical. Critical.

So you’ve created a false dichotomy, Jake, thinking if you’re using persuasion then you’re no longer using reason. That’s false. As the great Henry Boettinger wrote in his book Moving Mountains “Like a pair of scissors, no-one can say which blade does the cutting. The most you can say is both do it together. The same in persuasion. No-one can say whether logic or emotion cuts through inertia. The best you can say is they do it together.”

Now, you and other Tufte admirers may not understand or appreciate or even respect that sentiment, Jake. Maybe you’ve never been in a sales situation. Maybe you’ve never had to convince anyone of anything. Maybe your audience is 100% reasonable and don’t even care to hear your opinions. That’s fine. Then follow Tufte. But you do no service to yourself or others by having a “low opinion” of those do care equally about persuasion AND information.

—

Bruce Gabrielle

Author of the soon-to-be-published “Storytelling with Graphs”

@Gray… I often give people multiples levels to access the information… one level to get the general feel and a second level to get precise values… ideally these should be overlaid… see http://www.slideshare.net/jonbarrett/simple-techniques-to-make-your-message-stand-out-3017215

[…] The Pie Chart has been the pariah of the data visualization world ever since our well respected data visualization pioneer Edward Tufte condemned their usage. However, I, and others disagree. Bruce Gabrielle makes a series of compelling points and provides situations where Pie Charts are an ideal way to visualize relative relationships. Bruce’s counterpoint is located here. […]

I agree completely. The point is not always in precise comparisons, but sometimes, just about larger patterns, and I think Pie Charts do it well. I always have, and I understand the limitations of them.

I recently tweeted that Few and Tufte have begun believing the press releases they’ve written about themselves.

I once, but accident, created a chart with 270 pie charts on it, and the reaction of many was that–because they were pies–it must be horrible. But I think they are in fact instructive, if not very practical for every day use:

http://jonboeckenstedt.wordpress.com/2012/01/18/data-visualization-serendipity/

Jon – your feather chart is a clever way to visualize all that data as mini-pie charts. I always enjoy seeing innovative new ways to visualize data. Thanks for sharing and hope you’ll visit the blog often.

—

Bruce Gabrielle

Thank you for an excellent article. I think the reason for the dislike of pie charts is that they were used for everything and everywhere. Judiciously they have their place in dataviz.

Thanks Paul. You may be right that the pendulum has simply swung too far toward disliking pie charts, but that it is settling back to its midpoint again.

Late to the party…but wanted to add my thanks for a fantastic article.

We’ve shared liberally amongst the team here – great job, Bruce…

Wonderful to hear Simon and nice to see you at the blog!

Thanks Bruce – very thought-provoking post and subsequent discussion.

Nancy Duarte recently used a pie chart in a post on HBR, and there were one or two comments questioning its use. (Including from me!)

So having just found your post, I’ve now linked to it from a comment beneath Nancy’s post:

http://blogs.hbr.org/cs/2013/03/when_presenting_your_data_get.html#comment-853015245

Thanks for pointing out ways that pie charts might sometimes be useful. It’s refreshing to have subtleties discussed instead of “rigid rules” and “blanket bans”! (I admit to sometimes succumbing to those myself!)

Thanks for the comment, Craig. I myself in the past have made blanket statements like “pie charts are the junk food of the data visualization world”. But my opinion has evolved as I’ve dived into the research and observed pie charts that appear to work very well, despite Tufte’s dogma. I think it’s important for all so-called “gurus” to evolve their opinions as new information comes to light.

[…] Charts Chartbusters: Not Another Bad Pie Chart??? | Peltier Tech Blog | Excel Charts Maar ook: Why Tufte is Flat-Out Wrong about Pie Charts : Speaking PowerPoint Groetjes, Jan Karel Pieterse http://www.jkp-ads.com Medeoprichter van http://www.excelexperts.nl […]

I have an aversion to pie charts because when I worked at McKinsey they taught us never to use them; they were a sign of weak and imprecise thinking. They taught us to use bar charts, or when the proportion was what we wanted to convey, a sideways “waterfall” bar chart. We even had a special program that allowed us to make waterfall bar charts easily, because the Firm was so averse to pie charts.

I wonder how many of those who dislike pie charts today do so because of an early lesson from a place like McKinsey, and the stigma that attached to pie charts. I say this becaues I generally do prefer waterfall bar charts; however, as you say – and especially as your US multi-pie chart map illustrated – there are some situations when a pie chart is almost certainly superior.

I’m sure you’re right that many have an aversion to pie charts because they’ve been taught by experts or workplace cultures to have an aversion to them. And I agree with McKinsey that pie charts do a poor job of showing precise numbers.

But precision is not always important. For instance, what’s the market share for Windows, Apple and Linux? Windows clearly dominates with about 90% market share. You don’t need the precision of a bar chart to show that. A pie chart communicates that more quickly and with enough precision given the lopsided numbers. I haven’t seen a sideways waterfall chart but I can imagine that would also be effective.

May we have a pie chart telling Tufte et. al., how many people think he is wrong when it comes to pie charts? I think that would be swell.

[…] Today I ran across a really great, seemingly intellectually sound article on why pie charts are really good! Why Tufte is Flat-Out Wrong about Pie Charts. […]

I have written in support of your position, but never so well, so I blogged on your post and linked to a couple of your images in http://www.otusanalytics.com/wp/?p=2557. I don’t have a huge following but there are a few prominant folks that follow my blog. I wanted them to see a link to your post. Thanks!

Hi Mike – I appreciate your blog post and comments. Pie charts have their weaknesses, but also their strengths. They deserve more respect than they’ve gotten from the data viz world.

—

Bruce Gabrielle

I agree. When we launched our company, I sent an email to Stephen Few about trying to bring data visualization to the masses (ie everyone without $gazillion for software) because I think his bullet graph is really a good idea and *in general* his observations are sound.

I’m a hands on pragmatist who has several decades of experience with real people. Real people don’t read dashboard or BI BOOKs. HiPPOs read the book and then tell real people what to do.

If you need a 239 page book like Show Me The Numbers to “teach” people how to data visualize, ordinary mortals won’t read it and if they do, they won’t “get it”.

But HiPPOs will read it and tell them 😉

His reply to my email was unpleasant, just as his recent tirade of comments about Tableau have been unpleasant.

The cave paintings of our far distant ancestors lacked 3 dimensions but they told a good story. Telling a good story is all that data visualization needs to be, IMO (of course).

ANY visualization of data, IMHO, tells a better story than data in tables. Which is why we are trying to make it easy for anyone to paint their data elegantly, the way they want to, including pie charts and gauges, for next to nothing compared to everything on the market 🙂

Your post was well written and I’ve now subscribed. So I look forward to more pragmatic thought with great intelligent underpinning!

Thanks!

Mike – I especially like your focus on hands on pragmatists. I generally believe practitioners are smart and use the tools that, in their experience, helps them communicate. Wise experience is just as important as expert opinion and even research-based principles. I never ignore the opinion of practitioners.

When I first read the criticisms of Tufte and I Few, I was at first persuaded by their arguments against pie charts. But I also had to rationalize that with what practitioners are actually doing, and my own positive reactions to pie charts. So I think we need to be careful about following expert advice to the letter, and forgetting to form our own opinions.

Thanks for the comments and hope you’ll share your thoughts on future posts.

—

Bruce Gabrielle

Trying using a stacked bar chart for your argument about two companies domimnating 65% of the market. You are only offering a chart example that bolsters your case.

Additionally, the bar and line charts regarding men and women in class during the day quickly establish the ratio and trend without any gynmastics at all. By using pie charts, I am left comparing, well…slices of pie!

And for the couch example, why would you even need a graphic at all??? This is a double negative. 1 for Tufte’s rule and another for adding content to an advert that wastes my time trying to figure out what it represents.

I’m glad you agree. The pie chart does indeed bolster my case.

The pie chart is more effective than the bar and line charts, for the reasons I gave in the article.

The couch graphic quickly establishes the percentage “liking” for rounded vs square corners.

I completely disagree. You are using the incorrect bar chart in your comparison. Akin to drawing a conclusion from an insufficient or carefully selected dataset. Doesn’t pass the sniff test.

Additionally, the pie chart in the couch graphic is completely useless information to the message. It was succinctly stated in words, no other information needed.

There is no need for ANY chart in this advert so comparing one versus the other is pointless.

I’m using the bar chart Stephen Few used in his paper to discredit pie charts. I didn’t pick it; he did. And I agree with Few that if the purpose is to show precise comparisons, a bar chart is superior to a pie chart. But if the purpose is to show the combined value of two or more bars, a pie chart is superior.

That isn’t using an insufficient dataset, which involves removing or ignoring data that isn’t friendly to your argument. I’m ADDING to the dataset by including cases that illustrate when a pie chart is superior. And I am highlighting that portion of the dataset to illustrate my argument that SOMETIMES a pie chart is superior to a bar chart.

As far as the pie chart in the couch photos, it’s your opinion they are completely useless and it’s my opinion they serve a useful purpose. If you have something other than opinion to offer, like research results or illustrated examples, please share them.

It would be nice to have a LIKE or 1+ button for replies on Blogs. I’m with you, Bruce. In spite of the “data” that anti pie chart dogmatists use, terribly bright people and organizations continue to use pie charts- check out Google Analytics. I don’t know why. But it is simply a fact that they do. So that is our argument for offering a pie chart widget (and a gauge (horrors again) widget) with our dashboard software. Users find them useful to tell THEIR story. The rhetorical argument appeals to Ethos, Pathos, and Logos. Just based on popularity, for many people, the pie chart appears to have the more powerful appeal to pathos 🙂 On the other hand, our most important widget IS the rich text widget for adding (con)text to dashboards to tell the story, which adds a solid appeal to logos. It is our OPINION, that together, text and any chart data visualization is better than tables and text for telling data stories with appeal to pathos and logos. The ethos appeal comes, most often from the source of the data. Keep on defending reason and pragmatism.

Thanks for the comment Mike. I like your reference to logos, pathos and ethos. Charts in general apply to logos, but aesthetically pleasing charts like pie charts (and guages) also engage pathos. That’s a point many data visualization experts pay scant attention to.

Terrific discussion of all the key issues! As a member of the “hard-core scientific community,” I note that we scientists need to communicate clearly and compellingly just like everyone else. While science is indeed a noble search for truth, marketing our ideas is a necessary and important part of that search.

Hi Greg – I’m glad to hear you say that. I think there are 2 types of graphs – exploratory and explanatory. Exploratory graphs are meant to be studied so that questions can be answered and discoveries made. Explanatory are meant to be simplified versions to communicate the important insights that the scientist discovered. Education does a good job of teaching scientists and statisticians how to analyze data, statistical methods, exploratory graphs. But not how to communicate those findings to others.

Interestingly, business education suffers the same problem. We are taught how to analyze a situation and come up with a defensible strategy often based on data, but not how to communicate those ideas to others.

We need to recognize the difference between exploratory graphs and explanatory graphs. Audiences will appreciate the clearer communications.

—

Bruce Gabrielle

I think that’s a useful distinction. A common problem may be that what was originally made as an exploratory graph for one’s coworkers then gets re-used (due to laziness or convenience or whatever) in a presentation for a more general audience, when the graph really should be simplified for this new audience.

I really like this distinction – exploratory vs explanatory. I guess that most things start off exploratory and then move onto explanatory.

The presentations we do tend to be explanatory… explaining why we have come to the conclusion we have. We are then trying to really draw out and emphasise the conclusion of the data.

You are effectively ‘leading’ the audience so that they come to the same conclusion as you… which by some might be considered as somewhat controlling? But I guess you are only doing this because you believe this to be in the best interests of your client/audience. It would though make it more difficult for someone to spot other patterns/trends.

Hi Jon – Yes, exactly, you must lead the audience. Imagine Hans Rosling standing up on the TED stage and just running his Gapalyzer bubble chart in silence. Then he turns to the audience and says ‘Did everyone see that?’ Where am I looking? What insights should I draw?

No! You are the analyst but your job is to turn the data into conclusions that drive decisions. When you do that, you earn a place at the executive table. Does that make you somewhat controlling? Absolutely! But every communication is an editorial about what you think, supported by evidence. Graphs are very reliable evidence.

I like the insight Greg offered that too often we finish our analysis using exploratory graphs, then use THOSE SAME GRAPHS to communicate our conclusions to others. I think I’ll do a blog post highlighting the difference between exploratory and explantory graphs. I also plan to cover this distinction in my new book “Storytelling with Graphs”, which should be available in the next month or two.

—

Bruce Gabrielle

I hope this doesn’t end up sounding like a shameless plug for our product. But as I read how this dialog has taken a nice turn towards using data for communication and to tell stories, it makes me believe that we may be on the right track with our little startup. I say that because what you are writing is not only true for PPT presentations, but is also true of creating dashboards that drive performance.

Avinash Kaushik talked about this a few years ago on his blog “Occam’s Razor” in his post, “The “Action Dashboard” (An Alternative To Crappy Dashboards” http://www.kaushik.net/avinash/the-action-dashboard-an-alternative-to-crappy-dashboards/. “Know the difference between a Reporting Squirrel and a Analysis Ninja?

One is in the business of providing data.

One is in the business of providing, to use a old fashioned word, information.

This one of the core reasons why most dashboards are “crappy”, i.e. they are data pukes that provide little in terms of context and even less in terms of actionable value.”

Several of his posts were inspiration for how we designed the software. We put the emphasis on being able to create dashboards with context and then we added a Facebook/Google+ style discussion pane so that interactive dialog about the story in the dashboard can take place. And we jumped on his “heat maps in data tables” emphasis in how we designed “scorecards” for dashboards.

We believe that browser based dashboards should all evolve into effective interactive performance driving communication media – telling stories with graphs.

Very nice dialog here.

Yep. I run a market research firm and the phrase I live by is “Turn data into decisions”.

You want a seat at the executive table? Then bring conclusions, not just data.

—

Bruce Gabrielle

[…] an earlier post, I talked about this great post, Why Tufte is Flat-Out Wrong About Pie Charts. I posted a comment and started following further […]

Bruce, one other small note: the quote that you attribute to Tufte at the start of your post, though appearing on Tufte’s website, actually seems to belong to Martin Ternouth.

Thanks for catching that, Greg. You’re right, that link does take you to a Martin Ternouth quote. However, Edward Tufte originated that quote in his book The Visual Display of Quantitative Information (p. 178) and Martin is just using that as his base principle. But I’ve updated the link to avoid that confusion.

Here’s another link, showing the notes of someone who attended a Tufte workshop, capturing the same thought directly from Tufte.

—

Bruce Gabrielle

I once figured out a method of graphing multiple years of financial statements using a series of connected pie charts. See http://www.EnvisionFinancials.com.

Then I ran into Tufte’s and Few’s critiques. Yet, I kept seeing pie charts used by lots of people. I wondered how to put the two together.

Your have added needed clarity to the discussion.

Thanks

Thanks for the comment Jeremy. Your use of embedded pie charts is clever and clear, and another good example of how pie charts can compact a lot of information into a small space for comparison and analysis. Thanks for sharing that.

Another example of how Tufte is flat out wrong about pie chart.

—

Bruce Gabrielle

Thanks for the article. I was in the middle of designing a dashboard when I found your page. My dilemma was showing the comparison of staff mix (full time, part time, casual) between a department and whole company. My two bar charts didn’t really tell a story and the Few and Tufte books on my desk were judging my when I converted them to pie charts. I always thought that pie charts can sometimes be more effective at presenting data but your article backs up my opinions nicely.

Tufte is about presenting data to be interpreted. He is not about using charts to show part of the picture and get only part of the information acroos like 60% of the market is owned by company A and C. If that is the message you want to convey than type it in a sentence as you already did.

Why take up all of that space witha pie chart when you can type. ^0% of the market is owned by company A and C. Graphs are for displaying 20 or more data values in ways when it would be to wordy to write it or a data table is too much. You proved tuftes points with this article.

DONT MAKE GRAPHS WHEN BECAUSE YOU CAN ONLY WHEN YOU NEED TO. This is common outside of science and even in science it can occur.

I agree – Tufte’s advice has no place in a presentation to executives where the goal is to engage in a dicussion rather than to present data for the execs to interpret on their own. And graphs are a more engaging way to present data than a sentence.

—

Bruce

Hope I didn’t come across as mean. I agree with you as well. It can spice up a presentation. I justw anted to get Tufte’s back 🙂

Mike – it might be a cultural thing, but my experience presenting to executives is that it’s hard to engage them with a text slide and easy to engage them with a graph slide. Even if a pie chart just has a few slices, it has more impact than text.

For instance, I recently saw an executive slide showing smartphone market share, with Android and iPhone the two largest sections. That’s more powerful than a text slide that says “Android and iPhone make up a combined 60% of the market”.

And that’s the point that Tufte ignores: the emotional impact of graphs. And that’s what I wanted to highlight in the blog post.

I think Tufte has done a lot for the data viz world. But there are situations, like exec presentations, where his advice is off-base.

In summary it is incredibly insufficient two make a bar or pie chart with only two data values.

It may be good for marketing, but two data values can be written in a short sentence. Charts used to be tools to convey as much data as possible using the least ink and space and doing it clearly.

IE. what takes up more space.

Company A and C make up 60% of the market. Or a huge pie chart with a very simple message taking up much more space. It’s silly. This is what Tufte means!

[…] type of pie, Edward Tufte famously dislikes pie charts but Bruce Gabrielle calls him out and says Tufte is flat-out wrong, thems fighting […]

[…] type of pie, Edward Tufte famously dislikes pie charts but Bruce Gabrielle calls him out and says Tufte is flat-out wrong, thems fighting […]

It is interesting that a post such as this still generates discussion. I just came across it and what I respected the most is that there was an alternate view to Tufte’s or Few’s views of the data visualization, which for the most part have influenced many.

The other point that I also admire is that unlike some experts that are so strict on the “rules” of data visualization are ignorant to the audience’s capabilities of perceiving said visualization.

In other words, you can do everything right by following Stephen Few’s guidelines (or rules) and still have your audience not receiving your intended message. Sometimes a pie chart is all you need. Sometimes it is not.

If your boss, co-worker, client or employee gets enjoyment of a 3D chart (yes! I said it! wouldn’t use one if my life depended on it – but I said it) then so what? Tell the story of the data, don’t push it down people’s throats by restricting your creativity and that of your audience.

Kudos! Loved the article.

Thanks for your comments, Telmo. I do think the data viz world needs another respected voice to counter the dogma coming from Tufte and Few. We need a more nuanced understanding of when to use different types of graphs, rather than a one-size-fits-all kind of thinking. That voice is lacking today.

Glad you enjoyed the article and hope you’ll visit the blog often.

—

Bruce Gabrielle

[…] Why Tufte is flat out wrong about pie charts […]

[…] But there are contrary opinions out there as well. The high level points can be summed as audiences are more emotionally receptive to rounded edges than straight edges, and pie charts are more obviously demonstrating parts of a whole, where as a bar chart just compares discrete values not necessarily parts of a whole. Bruce Gabrielle talks to these points here. […]

[…] type of pie, Edward Tufte famously dislikes pie charts but Bruce Gabrielle calls him out and says Tufte is flat-out wrong, thems fighting […]

[…] Why Tufte is Flat-Out Wrong about Pie Charts : Speaking PowerPoint […]

Good article, Bruce. It adds a valuable counterweight to the “pie charts bad” point of view. I did find one glaring problem with your examples, though.

In section 2, the graphs about women vs men in early vs late classes dont any of them show what their titles claim to show. Without knowing how many people attend in the morning, afternoon, and evening, all you can claim is “women dominate mornings and afternoons, and men dominate evenings”. You have no information about when the men mostly attend or when the women mostly attend. Maybe the three times each have 33% of the women attendees, and the variation is all because of differential male attendance, or maybe vice versa, or any number of other scenarios.

Hi Craig – Great observation. You’re right, my summary that men are more likely to attend the evening classes is not supported by the graph because we don’t know how many men attended in the morning vs evening. The most I can say is that “women dominate the morning class and men dominate the evening class.”

Thanks for that important point of clarification.

—

Bruce Gabrielle

[…] have three pie charts to use in your lifetime, so choose them wisely,” however this article by Bruce Gabrielle makes some decent counterpoints worth considering (except the second point, pie […]

Yup. The hate for pie charts is often misplaced. I wrote a bit about is on http://workingvis.com/2013/07/22/every-now-and-again-a-pie-can-be-good/#more-94, but this article expands on the ideas and presents some great examples.

Hi Graham – I like your example of summing and comparing positive and negative values. As you say, a very common thing especially when reporting survey results.

—

Bruce Gabrielle

Thanks, yes. I’m not a huge fan of pie charts in general, but I do think they have been overly maligned. It seems fashionable to bash them. To me, I see more uses for them than other more trendy charts. In fact, an apt comparison might be to a tree map; both are, at their heart, asking you to compare geometrical properties that are not easy to compare (although I would suggest for a pie chart that people are comparing areas in a way that is easier than for differently aspected rectangles in a tree map) and yet, I see more situations in which I am likely to think a pie chart will work, than I am a treemap

Those that take Steven Few’s admonision on pie charts to heart need to do so. Those who understand what he is saying and when to intentionally ignore his advice are generally correct to do so. And those that ignore this advice… well, they are generally the ones that should have listened.

I do not diagree with your points, although I would have like to see some hard data on the useability of the different methods.

I am currently trying to change the presentation culture in a group that has used pie/3D/color to the point that presentations look more like the rainbow colored excrement of a herd of unicorns and less like professional presentations to drive rapid decisioning.

Saying no more “multicolored 3d pie charts” is a lot simpler than saying “… except when…” to a group that isn’t even aware of how bad their graphical communication has been.

No pie charts… except when you can prove they are more effective. Bring me proof the pie is better.

Perhaps We should hand out T-shirts with that statement.

Use of chart ? Easy, but false in 94% of case.

Pie charts is one of them ; )

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/article/20141114073802-11968090-94-de-vos-graphiques-sont-inappropriés

Faulty logic Pierre. 94% if you throw a dart at the dartboard of a 5×5 matrix but not if you know what you’re trying to say and choose the right graph to say it. Use pie charts to show percentage and to engage the audience emotionally.

Interesting article.

The A+B = 65% thing is demonstrably clearer in a pie chart than a non-stacked bar chart. But against a stacked? Not so sure…

The use of a line in the morning vs afternoon vs evening class I find very misleading. These are not time-series data, the data is discrete. It’s very confusing. In this scenario though, the pie does well. But it is space inefficient compared to just using the numbers.

If I’m presenting binary data I don’t use graphs. I generally use gigantic percentages above a full-bleed image. The image provides the ’emotional’ hit that’s missing from the pie. And if people want to drill into the data, they can look at their handout. Which has a table.

My approach for the map would be to use a heat map. Or to use bubbles (with color) – that way an additional data point could be encoded in a way that using a pie chart couldn’t. It would make the areas of the states clearer too (UK reader here, I’ve no idea where those boundary lines are :))

Like I said, these are interesting examples. But, my problem with pies is not that “there’s never a case for them”, but that I see them mis-used 99% of the time. I guess that’s where the (over)zealous hatred of them from the likes of Tufte and Few comes from, and they simplify away the scenarios where they have limited use.

Anyway, just my observations. I’m all for pragmatism, and I suspect I’ll use a pie chart again soon… but only when I’m totally sure it’s adding some kind of value!

Or you know, you could just use a pareto chart…+1 to Mike Ward’s comment – a 100% stacked bar or column would do this more effectively than the pie.

You absolutely can use a stacked bar chart instead of a pie chart. Or a waffle chart. Or a waterfall chart. Or any of the charts that break a whole into percentages.

But how do you decide? According to research, a pie chart is more effective than a stacked bar chart for estimating percentages, because it has an invisible scale at 25%, 50%, 75% and 100%. A stacked bar chart has no invisible scale. So what is the advantage of a stacked bar chart?

[…] crowd that pie charts are best avoided. Many pixels have been used explaining why pies are bad, when occasionally pies are good, and my personal favorite from my colleague at Darkhorse: Salvaging the Pie. Far less attention, […]

[…] main attraction to many users of the pie chart is the chart’s implicit suggestion that the slices are part of a whole. A reader looking at a pie chart of the American population […]

Hey Bruce, the article mentions an upcoming book called “Storytelling with Graphs” – did that ever make it to press?

Hi Mal – Thanks for asking! I’m a few months away from being happy with the final product. Still tightening the bolts on the ideas and the writing. Hoping for an early 2016 release (fingers crossed).

—

Bruce Gabrielle

[…] A defence of pie charts […]

Bruce – Thank you for an article that takes issue with several influential thinkers on data visualization. You make a reasonable case for pie charts in certain situations. My guess is that under these circumstances we quickly interpret pie charts because that’s the way we were introduced to simple fractions. As others have argued, the problem is this clarity quickly disappears as the number of slices increases.

In your example of market share, estimating how much company D controls from the pie chart is tricky and not worth the effort for A, E, and F. In contrast, the bars allow quick estimates for all six companies. Notice the trade off that the remaining data are rendered essentially useless by choosing a pie chart as the best visual for companies B and C. The information content of the pie chart is roughly 3/7 that of the bars assuming the message was each company’s share plus quickly conveying the importance of B and C. Again, I take your point that the pie chart is better if the message is really about B, C, then everyone else.

I’d echo the comments that the pie charts add little to the sofa graphic. I don’t find them to be helpful in the map either. A choropeth would work much better and I am not even sure that’s the best option.

Thanks for your comments Jonathan. You make a lot of assertions without proof. We call these “opinions”. Allow me to respond.

– Yes, the bar chart does allow for fast estimates of the lesser values, but slower estimates of the higher values. The bar chart also allows for slow realization that this equals 100%. Research proves both of these assertions. So that’s the tradeoff. The question is – how accurate does it need to be for the audience to engage in a conversation about it? If accuracy is highly important, then a bar chart is your best option. But maybe the pie chart is accurate enough and has the added benefit of quickly showing 100%

– The choropleth map would be great except for three things: 1) most people don’t have access to editable maps 2) the pie charts do the job nicely and 3) you have to learn the legend to interpret the choropleth map, vs just looking directly at the pie chart and not having to learn the legend.

– pie chart in the sofa graphic is merely a visual reminder, not meant to illustrate its superiority in this case

[…] data. Some of the most well known are the plain old bar/column chart, the much-maligned pie chart (for and against arguments. Personally, I think judicious use is ok), line charts and scatter plots. In […]

This is an old post, but I enjoyed it (congrats, Bruce)…

Why it’s so hard for understand, for some purists, that:

1. data visualization is mostly a marketing affair, in many corporations. So people may be using rather flashy charts to capture their audience. Your point that people like better round areas makes total sense. Add 3D, colors, gradients, etc, and you make everything more pleasing to the eye. I looked at people checking Edward Tufte’s forum (https://www.edwardtufte.com/bboard/q-and-a?topic_id=1) and Highcharts website. They left the first website in a hurry, but spent a lot of time on the flashy modern JavaScript portal. With those fat but yummy delicious 3D charts, yes! 🙂

2. purists used to come up with some outrageous and obvious negative use cases, and extended everything to “with so many bad examples, we should NEVER use pie charts again”. Wrong logic. For so many simple cases, with 2-3 categories, or event more categories, with visible difference between each slice, pie charts are and should still be the norm.

3. nobody really cares (or should really care), in a pie chart, if one slice is 1% larger or smaller than another one. These are obvious bad usage cases. Most cases however send a message about a VISIBLE approximation. When you have slice A half the size of B, nobody cares if A was 33% or 33.33%, or even 30% or 35%. The message sent by such pies is “A is about half the size of B” and that’s all. Some purists forgot most of the time we do not want to send exact precise information and we deal with approximations.

Thanks for the article Bruce.

Out of the five examples, you have given, in three examples you are comparing only two variable:

(Puts the audience in a positive frame of mind, Easier to estimate percentages, A line chart shows trends more clearly than side by side pie charts). I think pie charts can handle this simple scenario efficiently.

Regarding “A bar chart allows more accurate comparison than slices in a pie chart”, in Stephen Few’s article he describes it as a secret strength of the pie chart. But it depends on the order of the variables.

Regarding “Communicates part-to-whole relationship better”, I agree with you on for the pie chart it’s evident that the total adds up to hundred. But what’s the intent of the graph? If it is the meaningful comparison of the market share of different companies, bar charts are better for the same reasons in Few’s article.

It is not appropriate to compare business presentation slides with serious data visualisation because the complexity information involved doesn’t match.

[…] in business visualizations and there are people who are passionately against and enthusiastically for using pie charts. They are the simplest to understand and easiest to […]

[…] they might provide you with an effective part-to-whole snapshot, but what did that part-to-whole snapshot look like 3 months ago or last year? Instead, try […]